CHICAGO, June 13 – The two Hispanic teenagers in flip-flops and jeans clutched hands as they sat facing each other one recent afternoon, remembering the first moment they met.

It was the late 1920’s. They were Jewish immigrants from Odessa, a free-loving Communist aunt and her curious, admiring niece. Friends and relatives were crammed around the huge wood table for a family celebration.

“This is for you, for each other, Syl and Ruth,” David Feiner, the director, urged the two girls, who in fact met last summer through the Albany Park Theater Project, an improvisational troupe of young people in a gritty neighborhood on the Northwest Side of the city. “You can talk as loudly or softly as you like. I’d like you to tell each other your memory.”

The exercise was one part drama coaching, one part history lesson, one part political advocacy – a typical rehearsal recipe for the unusual theater company, now staging its 11th show of true stories stitched into a montage of dance and dialogue, spoken word and song. The current show, extended to this weekend, is an impressionistic chronicle of generations of Albany Park immigrants, from 19th-century German settlers to the day laborers who hustle on a street corner near the theater today, reaching a climax in the confessional of a member of the ensemble who is an undocumented immigrant.

Mr. Feiner and his wife, Laura Wiley, graduates of the Yale Drama School, founded the company, known as A.P.T.P., six years ago. They were trying to meld their artistic and activist ambitions with the motto, “Real teenagers, real community, real theater, real stories.” What has emerged, alongside a series of critically acclaimed original shows with a $10 ticket, is a family-like support group of about 35 teenagers that coaxes unknown talent out of many shy and troubled youths.

“Sometimes home isn’t the happiest place,” Marisa Ramierez, 18, the high school senior who belts out the throaty “Syl’s Blues” in the scene about the Jewish immigrants, which is based on the family of theater patron. “You can’t get everything you need at home. Here, there’s unlimited brothers and sisters, and there’s always food if you’re hungry.”

There are no auditions. Any neighborhood resident 13 to 21 who shows up is directed to the snack cabinet and incorporated in the company. The scripts are developed by the group through its collaborative storytelling, tape recording, transcribing and sketching out scenes on stage.

There are, however, sessions of intensive college counseling in which Mr. Feiner and Ms. Wiley spend dozens of hours with each graduating senior, researching colleges, preparing essays and visiting campuses. Of the 35 alumni who have gone to college, including the University of Virginia and Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., 90 percent were the first in their families to do so.

“I didn’t even believe in myself,” Nancy Casas, 21, a student at Beloit who spent four years in the company, said. “They were the first to believe in me. They see that you can go to college, even though you’re in this at-risk socially disadvantaged neighborhood. I really do not know where I’d be without A.P.T.P. Like the rest of my sisters, maybe, pregnant. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it’s not what I want.”

Nestled between the tracks of the el and the Chicago River 10 miles from downtown, Albany Park is a neighborhood of working poor, where 55 percent of the 50,000 residents are foreign born, reflected in the jumble of Arabic, Cambodian, Korean, Romanian, Spanish and Tagalog signs that dance down Lawrence Avenue. Half the population is Hispanic, according to the 2000 census, 19 percent Asian, 4 percent black and 23 percent “other.”

Ms. Wiley and Mr. Feiner raise the $200,000 that fills the snack cabinet, buys costumes and pays their salaries from foundations and corporations, as well as city and state governments. The theater, and the homey office where the teenagers flop on sofas and riff on keyboards between scenes, is on the second level of the Eugene Field Cultural Center of the Chicago Park District.

In addition to the shows and counseling, the couple also run a summer book club at their house on Sunday evenings, a weeklong camp for recruits, numerous outings to movies and museums and an annual retreat to places like Maine and Colorado. The couple attend graduations and birthday parties. They have bailed their actors out of jail for petty crimes, sought immigration lawyers, secured housing for a homeless cast member, taken another for an H.I.V. test and, recently, received the first call placed by a company member hospitalized for depression.

But the couple shun any suggestion that theirs is a do-gooder social service agency. They and the teenagers take the theater part seriously.

The current production began out of ethnographic exploration last summer in which the teenagers roamed neighborhood streets searching for stories. The opening scene, “Prairie, 1853,” stems from a photograph of Jacob Kunz’s farm that they found at the historical society. The spine of the show, “Amor de Lejos,” or “Love From Afar,” grows out of interviews that two young women conducted with the jornaleros, or day laborers, around the corner.

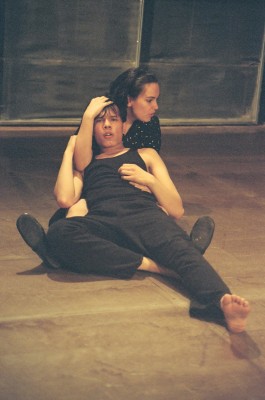

Five young men in paint-splattered jeans and work boots fling themselves across the stage in synchronized movements that simulate tiling floors and punctuate the main character’s monologue about his four harrowing attempts to cross the border. Choreographed mimes of shoveling, sweeping, painting, scraping and lifting bring the tyranny of work to life. Then a young woman in a buttercup sundress appears for a dream sequence, her skirt fluttering as she twirls around her displaced husband.

“There’s something very different about performing an actual person and performing a fictional character,” said Marta Popadiak, who portrays the jornalero’s wife. “It feels really good to be able to give someone a voice.”

Aqui Estoy (2003/2004)

The finale, “Nine Digits,” is adapted from the experiences of an unnamed company member who arrived at O’Hare International Airport from Colombia at age 6 and still lacks a Social Security card. It follows him through the humiliation of not having a driver’s license, the question of whether to marry for love or citizenship, the frustration of turning down an internship with a dance company in Washington and, ultimately, the admission to others in the troupe that he is here illegally.

“The war in Iraq began the same week we started rehearsals for this show,” says the character, played by Michael Nguyen, who describes two soldiers killed in Iraq granted citizenship posthumously. One “was from Mexico and, like me, did not choose to come to the U.S.,” Mr. Nguyen adds. “But was brought here as a child by his parents so he could have a better life.”

Jodi Wilgoren, New York Times

Menu

Menu