Chicago Tribune//Morgan Greene: “Welcome to the future home of Ellen Gates Starr High School,” announces Albany Park Theater Project co-founder David Feiner, smiling, unable to stand still.

“Whoooo!,” responds a crowd of Chicago public school students. They’re assembled outside a school building on a warm March day.

The group heads inside.

But what comes on the loudspeakers isn’t the morning announcements. Bastille’s “Pompeii” plays as the group begins an exercise akin to follow-the-leader but with enough clapping and stomping to kick up the dust in these mostly abandoned gray and yellow hallways, where Virgin Mary statues seem to pop out of the woodwork. Next on the soundtrack is Missy Elliott’s “WTF.”

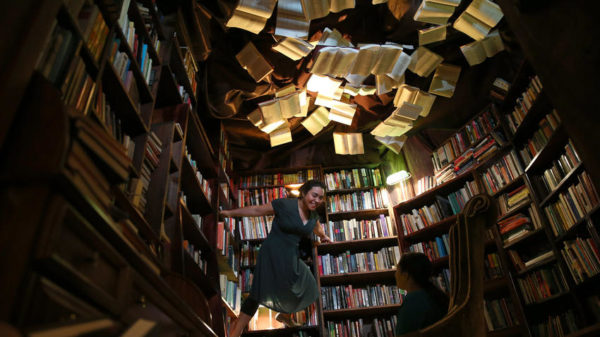

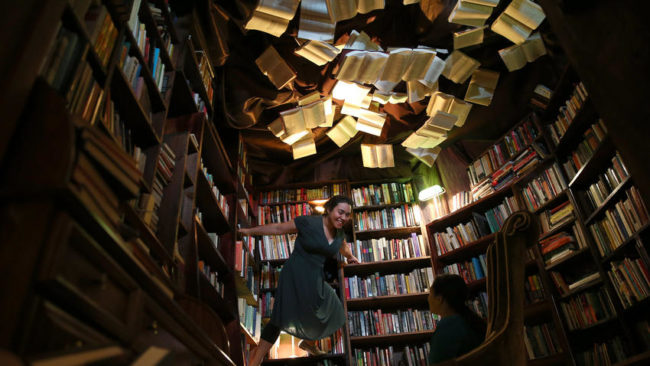

Ensemble member Maria Velazquez in the Starr High library. (Abel Uribe/Chicago Tribune)

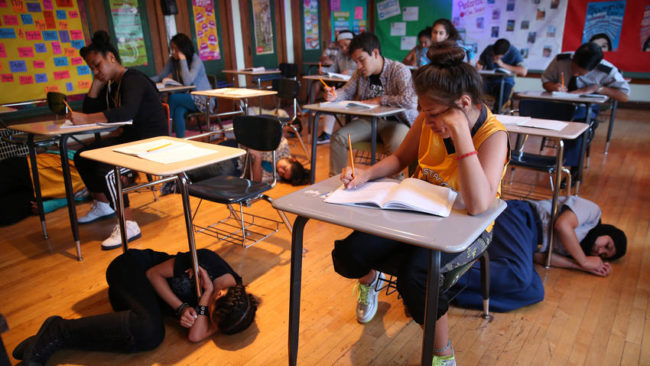

The collaboration is for a work titled Learning Curve, an ambitious, yearslong project that presents a day-in-the-life look at students in the Chicago Public Schools system.

Learning Curve began as a weeklong workshop, then a showing of works-in-progress at the company’s Eugene Field Park home in early 2015. The new production opens this weekend at Ellen Gates Starr.

The interior will become a four-floor jungle gym of reimagined classrooms. Guided by Third Rail members, students start to play as they begin testing out what can be climbed on, what can be hidden in and what familiar things can be made entirely strange. Carlton Cyrus Ward and [Edward Rice] demonstrate, turning a chalkboard into a tightrope and mounting a protective barricade made from rows of desks.

Out in the stairwell, Maidenwena Alba, a veteran APTP performer heading into her final year at Amundsen High School, slides down the stair railing to make a quick escape.

“Is this what it’s like all the time?” an APTP newbie asks.

Third Rail co-artistic director Jennine Willett, a co-director of Learning Curve, stops in one of the long hallways, its doors splayed open to create a shadowed, geometric tunnel.

“Wait,” she says, as she snaps a photo. “This is magic to me.”

Down the rabbit hole

Feiner knew he wanted to collaborate with Third Rail and Willett after he and his wife Maggie Popadiak (another co-director of Learning Curve) saw their now long-running hit Then She Fell, a mental ward-set spiral down the rabbit hole of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.”

“I remember walking out after the show and talking with three strangers on the street on the sidewalk in front of the ward,” Feiner says. “And after that conversation ended, Maggie and I just kind of looked at each other and said, ‘This changes everything.’ ”

Years after Feiner’s revelation, in the middle of April, I stand on that same sidewalk by the red-brick Brooklyn church building and prepare to enter Kingsland Ward, now in its [3rd] year of checking audiences in to Then She Fell. A man in a clinical uniform ushers me into a hallway adorned with vintage medical posters as an accordion plays through hidden speakers. The audience of 15 gathers in a waiting room and are offered a bittersweet alcoholic concoction, a welcomed gesture to those with more fluttery nerves. We are never together again during the show’s two-hour labyrinth.

But mirrors come alive, a man climbs the stairs upside down and I win a game of poker, luckily. In one of the more terrifying moments, I am tucked into a cot and a bedtime story is whispered into my ear. The lights are turned on to reveal a wall littered up and down with black tally marks, perhaps representing the days since I had first fallen asleep.

The experiences weave in and out of reality, but in every new moment, there is a guide extending a hand, drawing me deeper into the madness.

Coming together

In June, in a joint interview with Willett and Feiner at Ellen Gates, Willett recounts her own “aha moment” before working with APTP.

She came to see God’s Work, APTP’s dance and puppetry-fueled remount about a young girl’s escape from her abusive father, at the Goodman Theatre in 2014.

“I was like, we can really up the ante on this workshop,” she says.

So much of what Willett and Feiner talk about is how merging the two companies translates a day at a Chicago public school into a dream world of its own, by matching actual students that are part of an ensemble concerned with social justice with a company that revels in depicting otherworldliness, even that strange in-between world of adolescence.

“There are moments when you’re aware, even as a 15-year-old, of the way in which the macro issues of school and education and policy are limiting your life, restricting your life,” Feiner says. “And then there are moments when all of that doesn’t seem to matter and what matters is this really pressing thing that’s happening at home with your father’s immigration status. And then there are moments where what really matters is, ‘Do I look good today’?”

“It’s the Lynchian world of high school where you’re sort of going in and out of reality,” says Willett.

There are over 25 possible scenes to encounter in Learning Curve, with each audience member participating in roughly 60 percent of them during the course of a show. The nostalgia or current experience visitors bring will be their own.

“That’s the magic of being inside of something,” Willett says. “That you can’t separate yourself from it anymore.”

All-day rehearsals

By the beginning of July, thick cables hang from the ceilings at Ellen Gates. Spotlights peak out from corners and coats of bright paint cover the walls. By now there are more than 60 people involved in Learning Curve, including the performers. Soon Ellen Gates Starr High School will have its own website and Facebook page.

A group of APTP performers, now in rehearsal eight hours a day, five or six days a week, take a pizza break.

One of the newer members and first-time Learning Curve performer Alex Suarez, 16, says he wasn’t sure what he was stepping into. “I’m like, ‘Oh my god. I’m kind of scared that I have to join this,’ ” he says. “But, at the same time, I’m really excited for it.”

Few want to divulge their favorite moments in the show, not wanting to spoil any secrets. But Paola Rico, a 17-year-old senior at Roosevelt High School, speaks about one of her scenes, loosely labeled “body image.”

“Kids aren’t sad just because,” she says about the scene that activates every thought that goes through the minds of the self-conscious when they look in the mirror.

During the show’s workshops, Rico says she was stunned as audience members shared secrets, cried or even hugged her.

“You get a chance to see what people feel,” she says. “And you get to have a chance to comfort them.”…

The conversation turns to the subject of learning, and what an ideal education would look like.

The first request, shared by the entire group, is no standardized tests. They also mention support for arts programs. Education can and should be fun, they say. More hands-on activities. Smaller classrooms. And most of all: learning for the joy of learning, not grades.

On the way out, Feiner shows off a room-in-progress that will house a library scene. A maze opens up into walls of books; worn, shiny, fat, tall, all stacked one-by-one in dimly lit cases reaching to the ceiling. A bibliophile’s recycled dream.

Abraham “Kito” Espino, a longtime APTP performer, had talked about this scene. “In a world where education has become this scary, sinister kind of thing, the library feels like a light in the darkness,” he said. “It seems like you’re in a ‘Harry Potter’ world or something.”

All around are pages and pages of novels in limbo, suspended in time. Full of possibilities.

Menu

Menu